Czeslaw Milosz

Czeslaw MiloszOf Truth, Trauma, and Remembrance

I've been a little under the weather, so to speak, this week. Without going into needless detail, I've lost a great deal of faith in the decency and honesty of others, and it's worn me down a great deal. All I can do to understand what is happening is to get a grasp on the larger picture; I've been thinking about how cycles of lies and manipulation, in general, manifest themselves and how bystanders allow it to happen. I thought a lot about Holocaust denial, the secret history of California internment camps, and human rights violations being committed daily by this government at detainee camps. I came across a remarkable book by Doctor Judith Herman called Trauma and Recovery: The aftermath of violence--from domestic abuse to political terror. It really shed some light on the psychology of perpetrators and bystanders as they relate to the enabling of lies and manipulation:

To study psychological trauma is to come face to face both with human vulnerability in the natural world and with the capacity for evil in human natures...When the events are natural disasters or "acts of God," those who bear witness sympathize readily with the victim. But when the traumatic events are of human design, those who bear witness are caught in the conflict between victim and perpetrator...It is very tempting to take the side of the perpetrator. All the perpetrator asks is that the bystander do nothing. He appeals to the universal desire to see, hear, and speak no evil. The victim, on the other contrary, asks the bystander to share the burden of pain. The victim demands action, engagement, and remembering.

The author then goes on to cite psychiatrist Leo Eitinger, who studied Nazi concentration camp survivors. He says, "War and victims are something the community wants to forget."

The next passage identifies the ways that perpetrators silence victims:

In order to escape accountability for his crimes, the perpetrator does everything in his power to promote forgetting. Secrecy and silence are the perpetrator's first line of defense. If secrecy fails, the perpetrator attacks the credibility of his victim. If he cannot silence her absolutely, he tries to make sure that no one listens. To this end, he marshals an impressive array of arguments, from the most blatant denial to the most sophisticated and elegant rationalization.

The perpetrator's arguments prove irresistible when the bystander faces them in isolation. Without a supportive social environment, the bystander usually succumbs to to the temptation to look the other way...

Soldiers in every war, even those who have been regarded as heroes, complain bitterly that no one wants to know the real truth about war. When the victim is already devalued (a woman, a child), she may find that the most traumatic events of her life take place outside the realm of socially validated reality. Her experience becomes unspeakable.

I'm copying someone else's words right now because my own personal experiences with being lied to seem, at times, unspeakable.

But as for the world at large--in a few months, years, or even decades, will we choose to forget all the Iraqis whose lives our government batted around like bloodthirsty cats with half-dead mice corpses? Will we forget that we tortured innocent, honest men and allowed mercenaries to terrorize legions of civilians for sport? I feel like what Frank Rich said in a recent NYT article is true, that we are "a people in clinical depression." But do we all need to be mindless bystanders to lies, atrocity and evil?

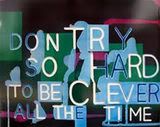

I'd like to believe that there is power in truth, and that people want to tell it. I'd rather think of the words of Czeslaw Milosz, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980, who said: "In a room where people unanimously maintain a conspiracy of silence, one word of truth sounds like a pistol shot."

I call on a preemptive remembrance of the truth. Starting now.

No comments:

Post a Comment